Palimpsest, Binder's Waste and Fief Law – Pragmatic Literature Part 7

In Sachsenspiegel and Schwabenspiegel

Palimpsest and Binder’s Waste

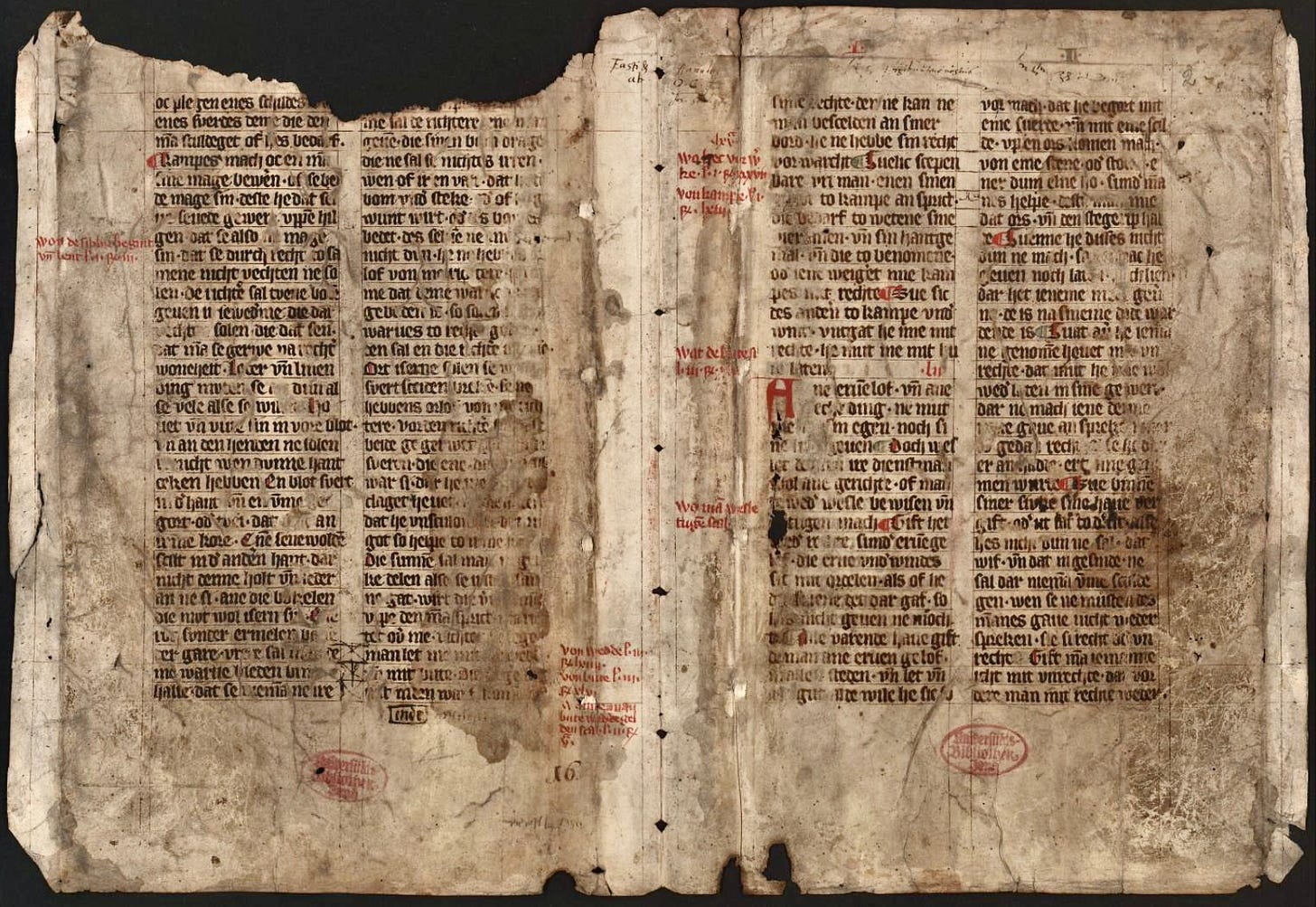

In Part 6 of this series about pragmatic literature, I highlight three medieval works which are one-of-a-kind because, among other reasons, their tradition comes down through just a single solitary manuscript, the loss of which would have meant works as significant as Beowulf or Hildebrandslied perishing forever. An estimated 80-90% of medieval manuscripts which once existed have been lost, destroyed or recycled. War, fires and carelessness have taken their toll. One can only wonder about possible great works which must have existed, but about which we will unfortunately never know.

Works as significant as some by Archimedes or Cicero are known to us from the ancient world only because they were fortunately recovered as palimpsest. This means the papyrus or parchment containing the text was recycled because it was deemed more valuable than the text it transmitted. The ink was scraped off for the writing material to be written over again. Modern technology allows researchers to discern the faintest images of scraped off writing so as to recover lost texts.

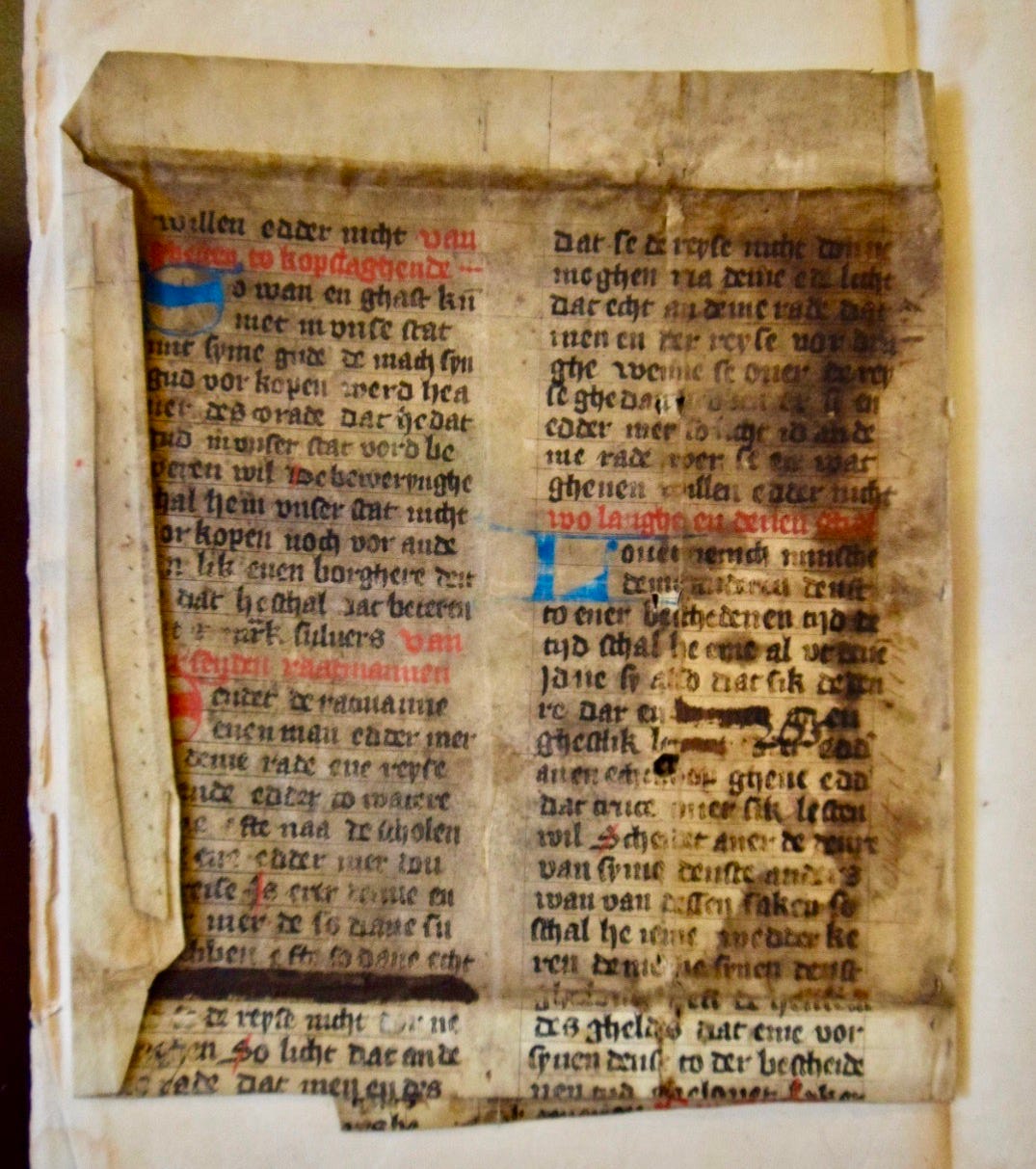

Another form of manuscript loss by recycling as well as rediscovery is binder’s waste or maculation, which is written parchment used to fortify the bindings or to line the spines of newly penned books, only to be rediscovered by archivists disembodying the particular codex centuries later. Even used parchment remains a costly and valuable resource in the Middle Ages to be recycled and never thrown away.

Classics and Bestsellers

In contrast to the rarest of unici like Beowulf, there are medieval bestsellers. Taking the attrition rate medieval manuscripts suffer into account, one surmises if a multitude of manuscript witnesses survive, then the actual production must have been as much as ten time greater. It is not unlikely that further Beowulf manuscripts once existed but were lost or destroyed. As much as ten surviving manuscript witnesses makes for a medieval bestseller because their existence implies up to 100 once having existed.

Remember, book production is exorbitantly expensive in the Middle Ages. Books are not bought at market, but are instead invested in through the patronage of princes, including bishops. Ten surviving manuscripts is a lot, not a little. Wolfram’s Parzival, discussed in my previous post, is one of the most viral medieval German language bestsellers, boasting 88 surviving codices and fragments. Its ‘international’ bestseller status is underpinned by the existence of medieval frescoes depicting scenes from it, located from Constance to Lübeck.

Not to be confused with a classic, a medieval bestseller is simply a work for which there was high demand and of which there was accordingly high production. One of the biggest bestsellers of medieval German literature with 65 manuscript witnesses, Meister Albrant’s Roßarzneibuch, a veterinary book for horses, was not popular because of its literary quality, but instead because of the practical demand put on it as a book to be used. The tradition of Hartmann’s von Aue Erec, an epic he based upon Chrétien’s de Troyes Erec and Enide, comes to us through only four manuscript witnesses; therefore is not a bestseller, but still an indispensable classic.

The ‘anonymously’ written Nibelungenlied — or Lay of the Nibelungen — is, like Parzival, both a classic of medieval literature as well as a bestseller (transmitted by 37 manuscript witnesses). Determining a work to be a classic is a matter of the literary canon, arrived at through the consensus of literary scientists. Not by merely a matter of taste, a canonical classic is a work judged by experts significant enough to never ignore because of its aesthetic qualities and cultural significance. Canonical classics are academics’ ‘must reads’. In upcoming Part 8, I will examine the transgression of both spatial and legal boundaries in the medieval classic the Nibelungenlied.

The Medieval Genre Problem

If the Nibelungenlied, Parzival and Gottfried’s Tristan (with 30 witnesses) are bestsellers, then Eike’s von Repgow Middle Low German law book originating around 1200, the Sachsenspiegel with 424 surviving witnesses, is by far the biggest blockbuster bestseller of the German speaking Middle Ages. Its Middle High German adaption Schwabenspiegel comes in next with 404 manuscript witnesses. Spiegel means ‘mirror’ and is used in the same sense as a mirror for princes — specula principum — an instructional text for Saxon rulers.

Although the fictional genre poetic epic captures the bulk of researcher’s attention, it represents only a fraction of the tradition of medieval German language literature, mostly consisting of religious texts, law, medicine and other pragmatic reference material like chronicles, didactics or even recipes.

Classifying the German language literature of the Middle Ages into genres is not entirely arbitrary, but can be confusing or even besides the point. Medieval genres are amorphous and ambivalent in a way. There is a kind of overlap between medieval genres compared to modern ones. All medieval literature, even law and medicine, exists before the backdrop of religiosity. Therefore, there is no non-religious or vaguely secular medieval literature, regardless how worldly its subject matter may be.

Chronicles, which belong to reference, contain their share of fiction, ie. Nero gives birth to a frog in the historical work Kaiserchronik. On the other hand, epic poetry like the Nibelungenlied, unambiguously considered fiction today, relays factual historical events and depicts real historical figures, even when mixed with blatant fabulae, like Siegfried’s tarnkappe, which can render him invisible: a magical hooded cape (not a ring).

Law in the Vernacular: Sachsenspiegal and Schwabenspiegel

Medieval law books are unlike their modern equivalents in countless ways. They have no legal authority like we understand it today, nor do they originate from the mandate of elected lawmakers or rulers, but instead from unauthorized innovators such as Eike von Repgow. Not unlike historical chronicles, the statutes of medieval law books often convey past events, but in other ways. A statute was often first codified because the behavior regulated became a problem in an unusual circumstance, ie. statutes sanctioning manipulated scales at market were only written down because a scale was indeed manipulated.

A local statute proscribing where a town’s firewood is to be stacked, for example, give us a tangible view into a locality’s past. Because the codification of laws arises out of a need to mitigate real problems, one imagines that leaving such arrangements unregulated may have once led to catastrophe, ie. stacking firewood too near houses may have caused the town to burn. Regulation really transpires through custom, but writing statues down serves not only as a reminder, but also as an appeal to the communé for consensus-building. In the Middle Ages, law books tend to coax more than compel.

Despite the universal truth concerning medieval law claimed by Eike in the Sachsenspiegel: God is selven recht — God is himself the law — law is actually fictional. It is invented by people, even when it is built on and justified by the foundation of Holy Scripture. 20th Century Philosopher Hans Vaihinger points out the fictionality of law in his The Philosophy of As If. Both poetic epic and law serve as a negative exemplum, a demonstration of how not to behave. They warn the recipient of consequences for transgressing against accepted norms. Jacob Grimm, philologist, linguist and occasional collector of Märchen — fairy tales — makes the apt observation: “poesy and law arise from the same bed”. Both tell stories and there is no separating them.

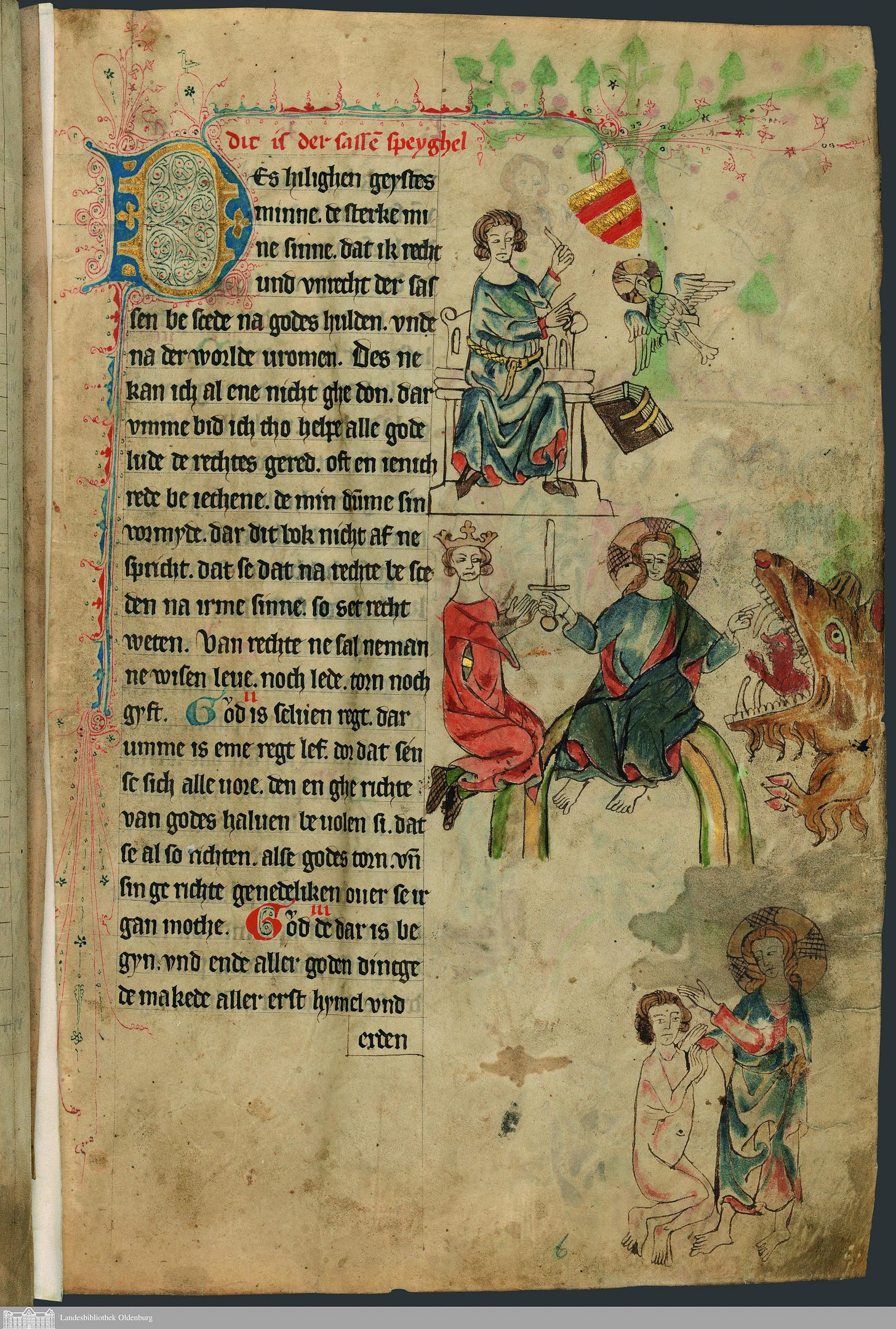

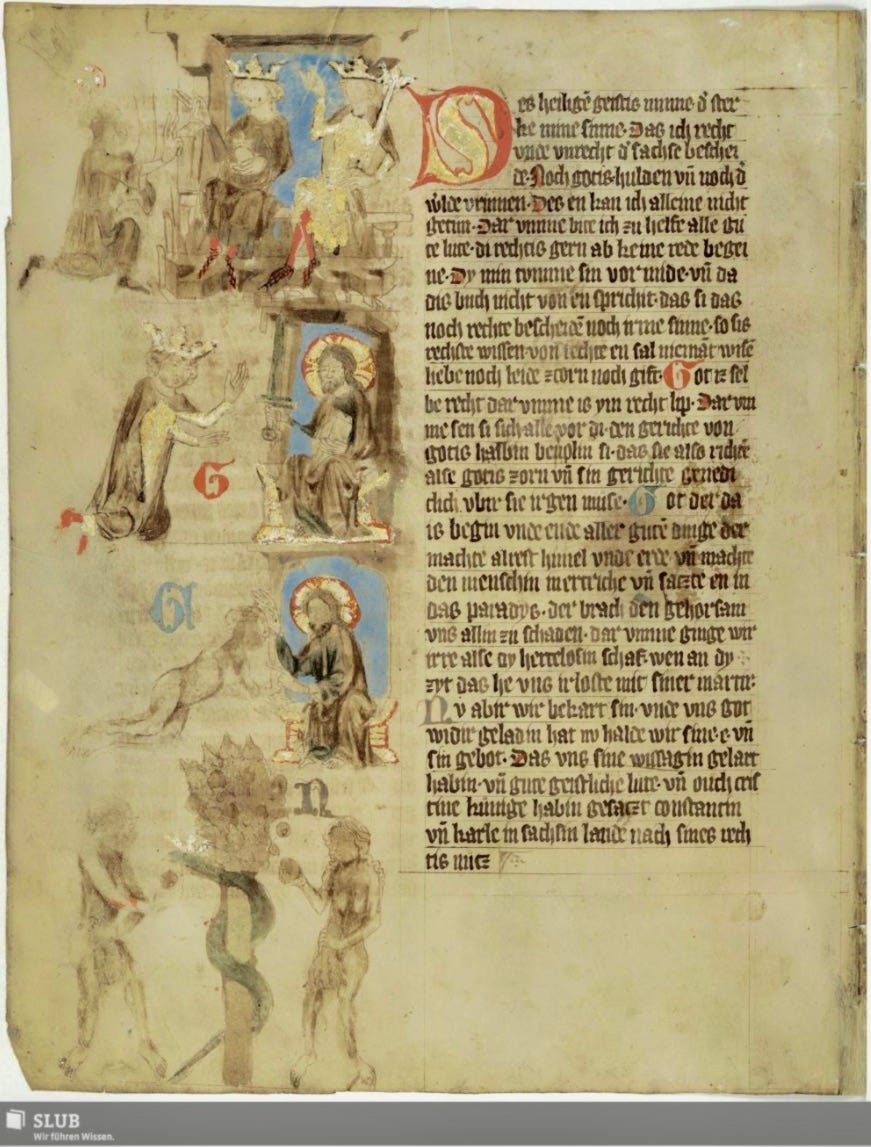

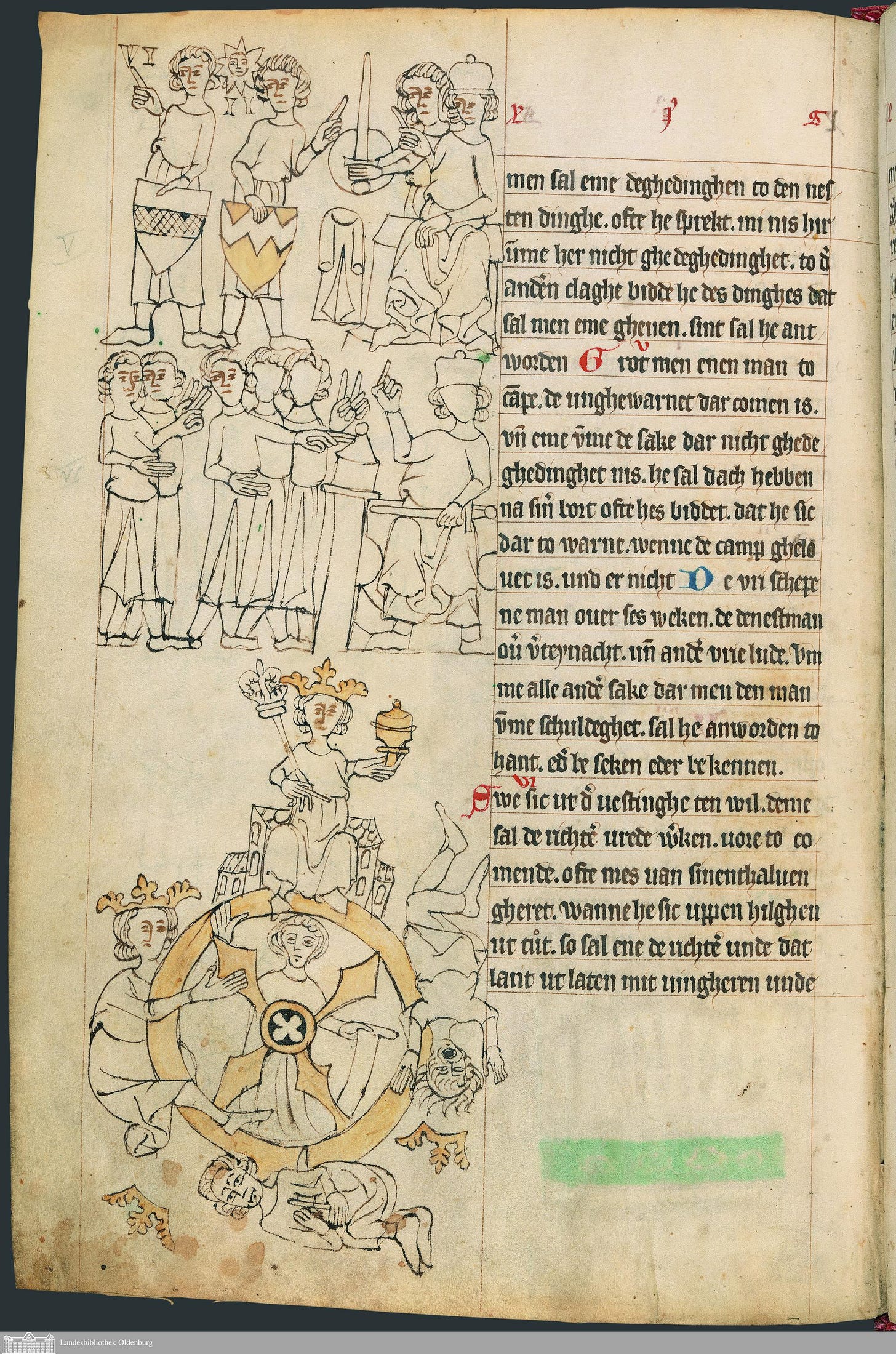

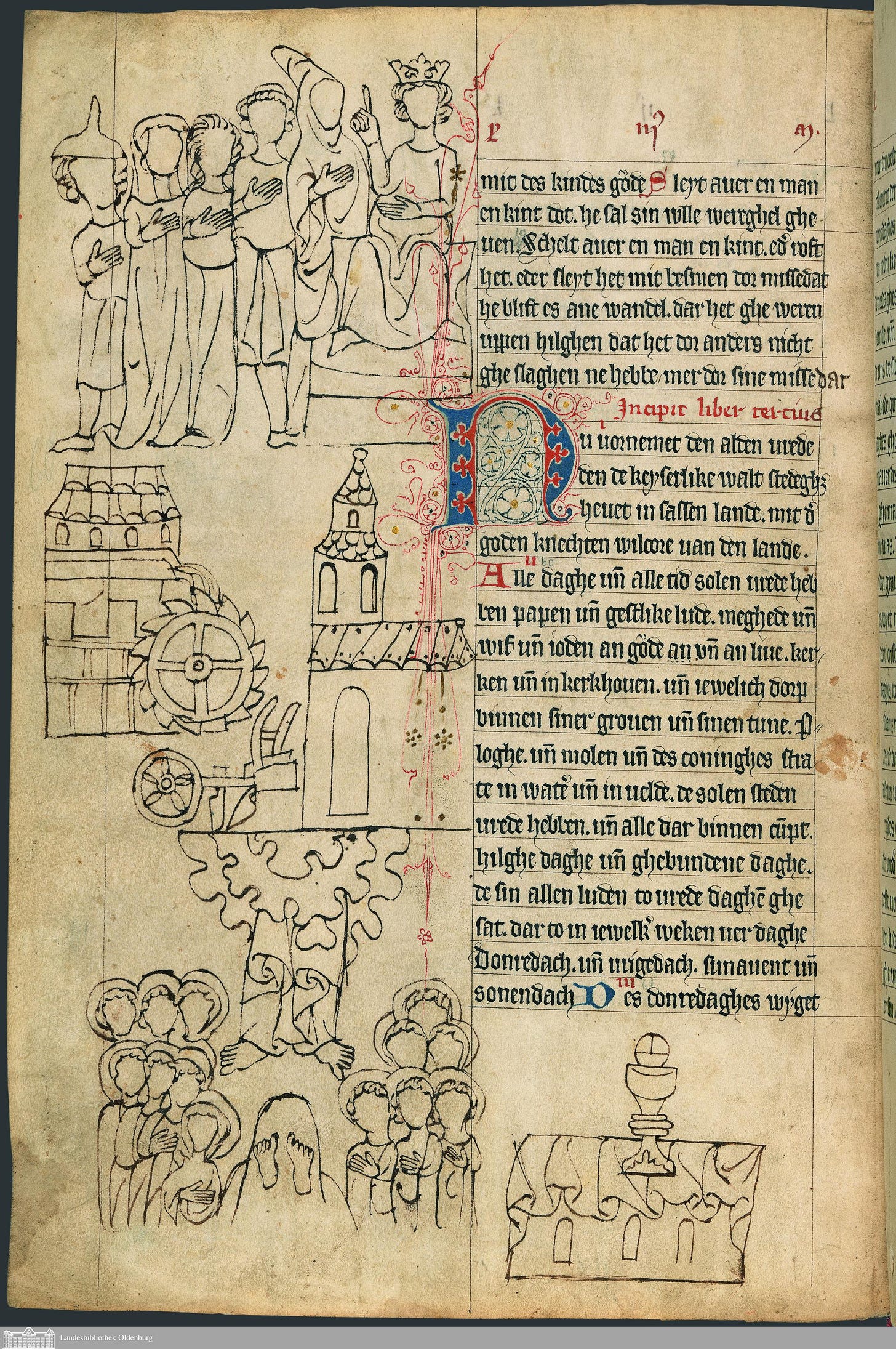

Despite law’s fictionality, in the Middle Ages, it is nevertheless still revealed law — lex divinum — which ultimately hinges on the authority of Holy Scripture delivered by the Holy Spirit. Books, as well as law, are ineluctably connected to God in the Middle Ages, as can be observed on the opening folia of the famous Oldenburg manuscript as well as the illustrated Dresden manuscript pictured above. A medieval illiterate can well follow the illustration depicting the Holy Spirit as a dove delivering the scribe Eike a book, as well as Christ seated as judge, the sword of justice in his right hand. A member of the elite initiated into literacy reads the invocation headed with the introductory rubricized line, then starting with the large D lombard initial richly decorated with flueroneé.

dit is der sassê speyghel

Des hilighen geystes

minne. de sterke mi-

ne sinne. dat ik recht

und unrecht der sas-

sen be scede na godes hulden.

this is the Saxon’s mirror

by the love of the Holy Ghost

which strengthens my wits

so that I can discern between

right and wrong among the Saxons

according to the grace of God

The Sachsenspiegel and Schwabenspiegel both consist of two main books: Landesrecht and Lehensrecht — Land Law and Fief Law. The former handles legal questions concerning unfree people, the latter those concerning free people — freyer leut— ie. property owners, knights, priests, vassals and princes. The Land Law applies to unfree male and female peasants – knechte and maget – their children as well as tax collectors and the servants of free people — dienstmanne or dienstleute. These are not separate physical books but several parts of one codex, much like books of the Bible are contained in one volume.

The Sachsenspiegel is civil law, which addresses questions of property, inheritance, the wardship of orphans, contracts, liability for damages, and court proceedings. It has no jurisdiction as we understand it today but is rather a resource upon which to freely draw in the Middle Ages, when different law can be chosen from, as though from a menu, and forum shopping for courts is routine.

In regards to the second part of the Sachsenspiegel, the Fief Law: historian Elisabeth Brown rightly criticizes the use of the f-word, prevalent in Medieval Studies in the 19th-20th Centuries, as superfluous, especially in older, outdated French scholarship, which falsely imagined the existence of a system of medieval law concerning “vassalage, fiefs and service in arms” . https://alatinacolonia2013.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/brown-tyranny-of-a-construct.pdf

However, there were, of course, vassals, fiefs and service in arms in the Middle Ages, the rub being these do not constitute anything like what we understand today as a system. Eike does not even portend to establish a legal system with his Fief Law book. The f-word is indeed useless and even misleading, but not because the phenomena it attempts to describe did not exist. Historical documents like deeds, charters, oaths and contracts incontrovertibly prove the existence of these sworn relationships, sometimes involving the transfer of property. While fiefs exist, not all fiefs are created equal. Outdated scholarship saw medieval affairs through the modern lens of presentism and erroneously sought to describe them using the modern paradigm of the ‘system’.

The once itinerant knightly poet Walther von der Vogelweide composes a song: Ich hân mîn lêhen — “I have my fief”, celebrating receiving a fief from a kind lord, leveling him up socially as well as saving him from February’s freezing cold. It is not a homogenous system through which Walther becomes a property owner, but instead it is through a certain patronage relationship he develops. His humble fief likely had almost nothing in common with a Bishopric, which is also a fief granted by a ruler. One size does not fit all in the Middle Ages. Everything is made to order.

The f-word’s -ism suffix is what presents us with the problem at hand, because it imagines the phenomena of sworn relationships to consist of a system with rigid institutions and rote procedures, which generally do not exist in the Middle Ages. Systems in the form they take today are foreign to the medieval world in which legal considerations and contractual agreements are fluid and negotiable. They are encountered as optional and are subject to improvisation. They are not compulsory and fixed. The swearing of oaths may be the only institution to serve as a common denominator amongst a great variety of heterogenous legal considerations, and even it takes on many forms. Ultimately, the law is what a judge verbally says and what the outcome in court is, not what is written in a book. In the same oral tradition of legal practice today, a modern judge pronounces a verdict verbally to enact it and does not merely hand it off on a piece of paper.

Written law serves as a guideline for legal decisions in the Middle Ages but does not wield binding authority. It does not put demands on a judge, but is instead a resource for him to turn to. Contracts are not formal, but the terms are instead always negotiable between the grantor and receiver of a beneficium (fief). In the Middle Ages, there is nothing like a homogenous compulsory legal system governing these circumstances, forget about -isms, even when we have a Fief Law book before us.

The Sachsenspiegel is revolutionary because it carries knowledge previously only accessible in Latin over into the vernacular. The second book, Fief Law, is preceded by its Latin prototype Auctor vetus de beneficiis. The milieu Eike appeals to, lords and knights of the second estate, are not educated in Latin and literacy as are their younger brothers, who are set on a clerical instead of a military career course. The Sachsenspiegel represents a blow to the gatekeeping of the Latin speaking elite and widens the circle of people given access to a better understanding of law, even when they are also elites but of a different sort.

The structure and much of the content of the Sachsenspiegel are indebted to the Code of Justinian — iuris civilis — which is introduced to the medieval world through the University of Bologna in the 11th Century. Not only professors and students of canon law transmit this knowledge, but scribes also acquire education in legal matters and procedures at cathedral schools, sometimes even as autodidacts. ‘Scribe’ – secreterum or notaris — can be a high office in the Middle Ages. Scribes not only write, but sometime function as legal advisors and even diplomats: syndicii and nuncii. Eike must have been such a scribe educated in legal matters, likely at the cathedral school at Halberstadt or Magdeburg.

While some orally transmitted German customary law seeps its way into the Sachsenspiegel, this in no way makes it ‘German law’. The word ‘German’ refers only to languages and language groups in the Middle Ages. There is no conception of German people or territories until 1500 under Emperor Maximillian I. The idea of a German nation will be first galvanized as late as 1870. There is no medieval reference to the use of the word ‘German’ — deutsch or diutisch, tiutsch etc to describe a people or territory analogous the Bede’s use of the term gens Anglorum, the English people.

Jacob Grimm, a 19th Century Romantic endeavoring to help establish a lacking German national identity, exaggerates the significance of Eike’s choice of language while not recognizing the prominent role Roman law plays in the Sachsenspiegel. Eike explicitly writes his book for the Saxons who speak the Saxon Low German dialect. If the law book does function to forge new identities, it is not for a German people but instead for the Saxons, one particular language group. The Schwabenspiegel is translated for the Swabians into their dialect, while the content of both law books runs parallel.

Medieval German dialects are, in general, facsimiles of distinct languages while Low German is a completely different language more similar to English than High German in significant ways, ie. like English, it did not undergo the second consonant shift which High German did. The second consonant shift was discovered by the Grimm Brothers through their study of Sanskrit, which is a distant relative of the Germanic languages including English.

Eike depicts the law as practiced in his direct Saxon environment near Dessau. If there is any kind of ‘national’ consciousness in the German speaking Middle Ages, it is held by smaller language groups who understand themselves as Saxon, Frankish, Bavarian, Allemannic et al and certainly not in terms of modern nation states, which will not exist until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

Parallels to Emperor Friedrich’s II Landfrieden — Public Peace of 1235

Emperor Friedrich II issues the Public Peace decree — Landfrieden wyllekor — in 1235 at Mainz with the objective of halting the practice of the feud to settle differences. The decree sought to replace the custom of arbitrarily acting out revenge as an answer to damages suffered — with court proceedings to determine compensation for them. While not directly connected, the Sachsenspiegel also moves in this same direction at the same time.

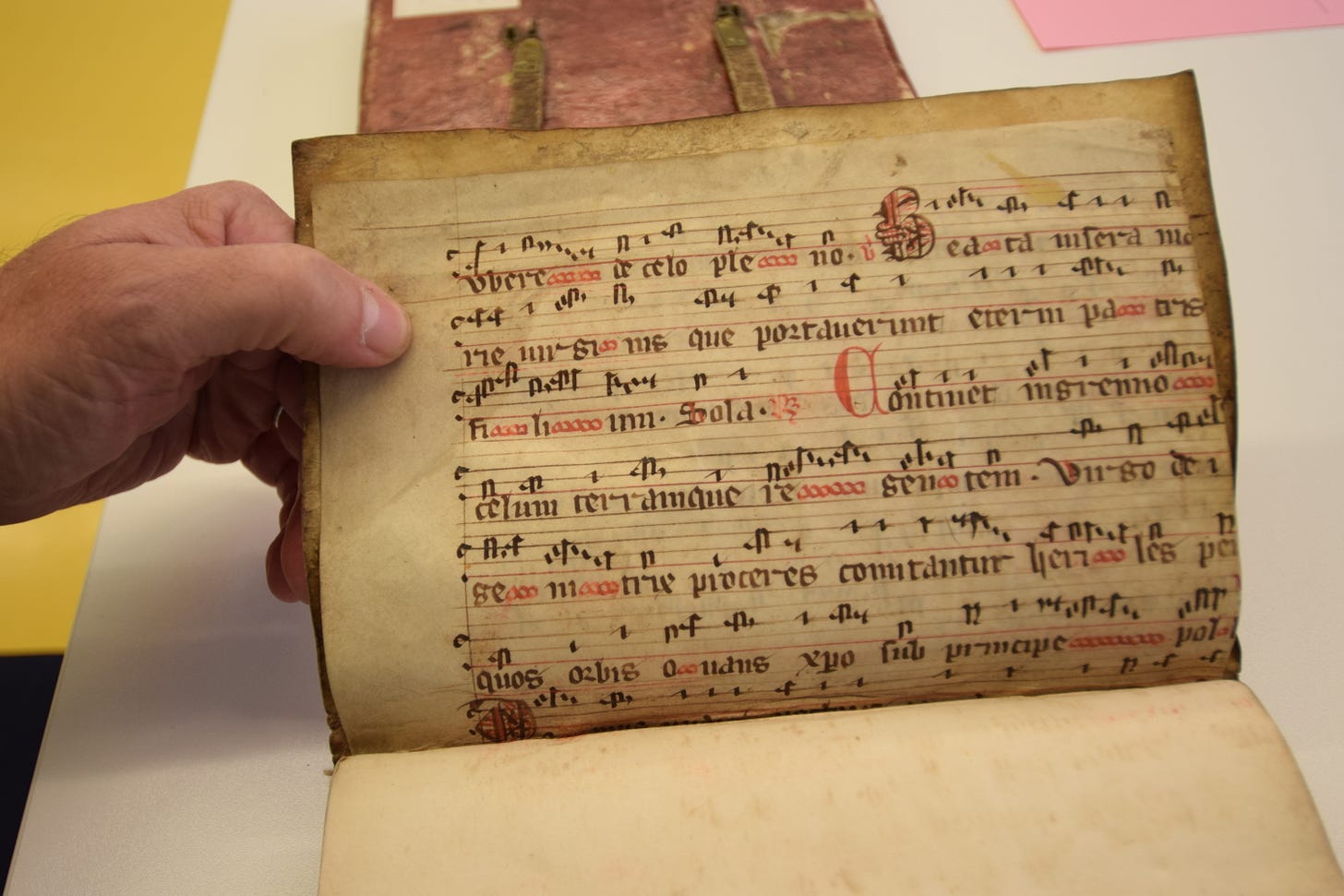

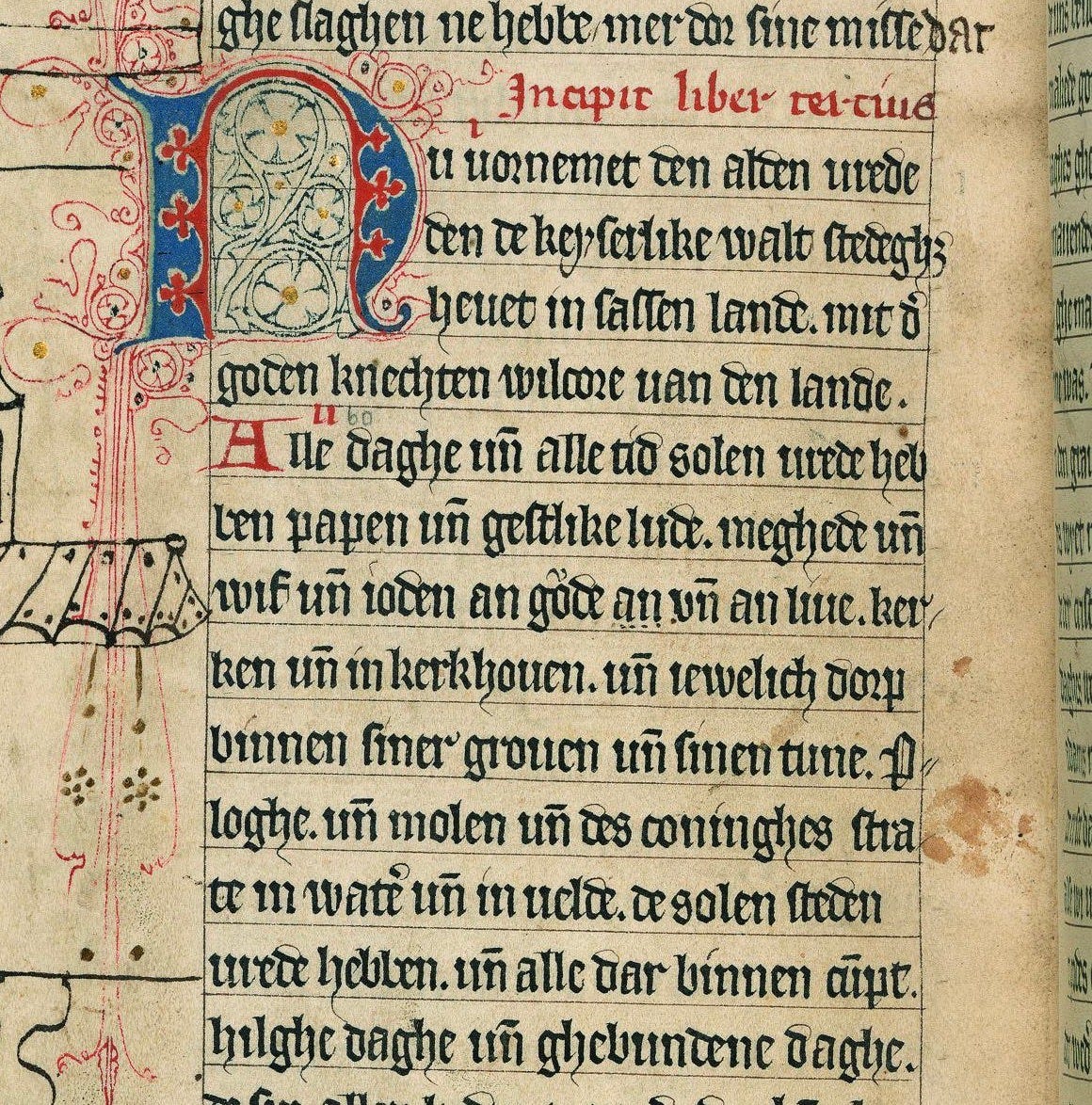

From the Fief Law beginning with the large rubricized A initial pictured below:

Alle dhage und alle tid sollen vrede heb-

ben papen unde gestlike lud, meghede und

wif und ioden an gode an und an irem live ker-

ken und kerkhoven und iewelich dorp

binnen siner gruven und simen tune P-

hloge und molen unde des choninghes stra-

te in wate und in velde de solen steden vrede hebben

und alle der binnen cupt

Peace shall prevail everyday and at all times

Priests and clerics, maids and women

As well as Jews, in their rights and bodies

Churches and churchyards and every village

Within its moats and walls

Commons and mills and the King’s roads

Along water ways and fields, they shall always have peace

And everything which comes with it

In upcoming part 8 of this series about pragmatic literature, we will look at a scene in the Nibelungenlied in which lords, vassals, pages and servants who have sworn relationships are depicted. A lord’s vassal, Hagen, breaks the peace against a priest. Hagen’s lord, Gunther, promises the priest compensation for the damages suffered at the hands of his vassal. Hagen and the Burgundians will face the greater consequences of an ill fate at Attila’s court, however, as Kriemhild takes revenge on him for far worse crimes. The story tells of a bloody, vengeful feud, perhaps as a negative exemplum.

There is something about illuminated pages from so long ago. I know someone held and read these pages. And I know people then marveled at art on paper and in a book! Beautiful reminders of a history long gone but yet people just people who owned, read, and cherished their books as I do today. Thank you for sharing these gorgeous pages.