Copiar books or cartularies are ‘house books’ of medieval chanceries in which incoming materials are recorded. These books are used for the administration of whatever institution a particular chancery serves. Initially, during the Early Middle Ages, this would exclusively be a bishopric or a monastery. In the wake of the great City Boom of the 13th Century, driven by the upcoming merchant class, it could equally well be the chancery of a city administration. Worldly rulers like dukes or kings are the last ones to come into possession of their own chanceries. The merchant class of burghers, which also includes craftsmen, is often overlooked in Medieval Studies. Scholars find the first and second estates, clerics and knights, more alluring. A chancery, while also being a place which produces writing, differs from a scriptorium in so far as it is a place from whence written documents like letters, privileges and deeds are sent for administrative purposes. Remember, this is pragmatic literature: literature which serves concrete, and sometimes less concrete purposes.

The burghers become key players in promoting literacy and the use of writing, books and letters starting in the High Middle Ages. Writing makes the exponential growth of cities during the 13th century possible. Only with writing can merchants become sedentary during this epoch, living year-round in one place with the newfound ability to correspond over great distance and to keep records. Merchants hire freelance ‘chamber scribes’ trained by cathedral schools for these purposes, before they are granted their own independent schools by bishops, thereby becoming fully literate themselves. Latin is still almost exclusively used. Previously, the illiterate merchant’s lifestyle was a traveling one, traveling from fair to fair throughout the year: ie to Champagne, then to Frankfurt. Their law was orally transmitted.

In Northern Europe, the acquisition of writing by merchants lets them form small companies, mostly consisting of two partners corresponding by letter, each in a disparate location: ie one brother in Hamburg, the other one in London, or an uncle in Cologne and his nephew in Bergen. One can construe a kind of proto-capitalism emerging in Italy during the 14th Century around banking, the Medicii family and textile and metallurgy production, which begins to overstep the bounds of the family-based cottage industry. In the North, however, a trading company is strictly a tiny family business, which typically lasts for as long as its usefulness or convenience lasts, often dissolving and reforming to suit the new unfolding situation. The resilience of this system allowed the Hanseatic League — an informal association of trading cities along waterways in Northern Europe, especially along the Baltic — to flourish for as much as 400 years.

Lübeck, the center of the Hanseatic League, is situated on the mouth of the Trave in the Baltic, the perfect place for trade between it — reaching all the way from Novgorod in Russia, supplying furs, wax, honey and lumber — and the North Sea: to Flanders, England and France, with their rich textile, wool and wine trades, respectively. Salt and herring are also big business because of the tradition of the abstinence from meat on Fridays. Lübeck’s ascent is nothing but meteoric, going in a short time from nothing but a hill between two rivers to one of the biggest cities in Europe, rivaling the populations of Cologne and Paris. Lübeck is founded as a planned city by Henry the Lion of the Welphs, son-in-law of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Henry the Lion is forced into exile to London with his wife Matilda of England in the aftermath of his conflict with soon-to-be Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa of the rival Staufers, who puts the city under siege in 1181.

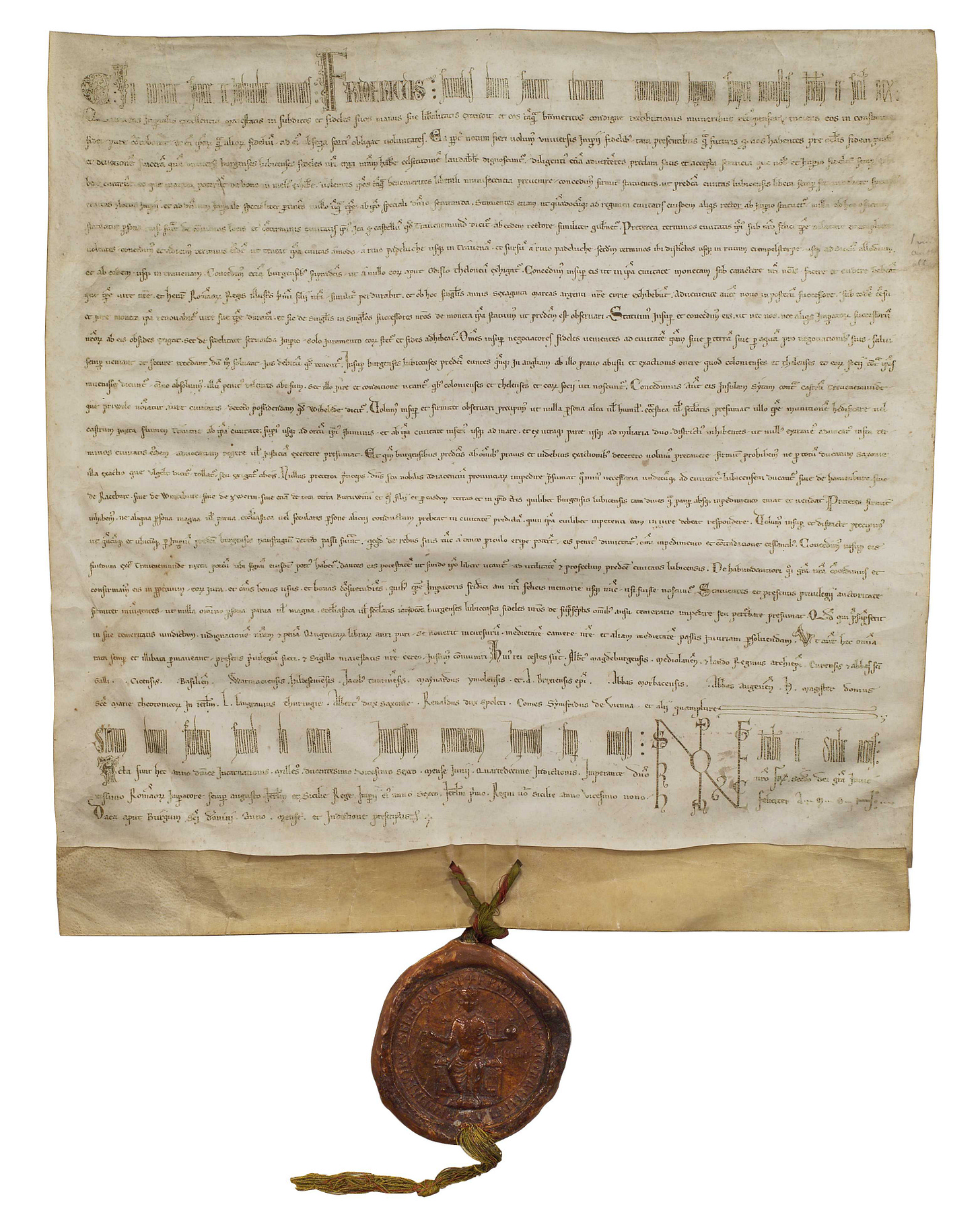

The wealthy merchants who make up the Rat — the City Council — are quick to strike a deal. Barbarossa grants them a privilege, offering them imperial protection, allowing them freedom over trade, markets, coinage and their own law-making. They do not flinch at changing sides and forsaking their founding figure, Henry the Lion of Brunswick, if this fateful opportunity could be massaged in their favor. Barbarossa’s grandson, Friedrich II, extends this privilege in 1226, elevating Lübeck to the first imperial city. The wealth generated by the dynamic port-city makes it into an apple of Friedrich’s eye, but a distant one. He spends most of his time in Italy. The Emperor is willing to give the burghers of Lübeck all the latitude they want, if he can keep their catalyzation of trade in his orbit, albeit a far-away one.

This is the time in which the merchant class rises up onto an eye-to-eye level even with the Emperor, as contenders with spiritual and worldly powers, the first and second estates. The cultural production of the new merchant class is, while often overlooked, of great significance for the future we now know as our free and open society. The burghers are the first ones to break the culture and literacy monopoly of the religious institutions, formerly the exclusive gatekeepers of the written word during the Early Middle Ages. This faltering of the clergy’s monopoly on literacy gives rise to the nascent stage of the educated bourgeoisie, the Bildungsbürgertum, a designation which would describe the denizens of Substack.

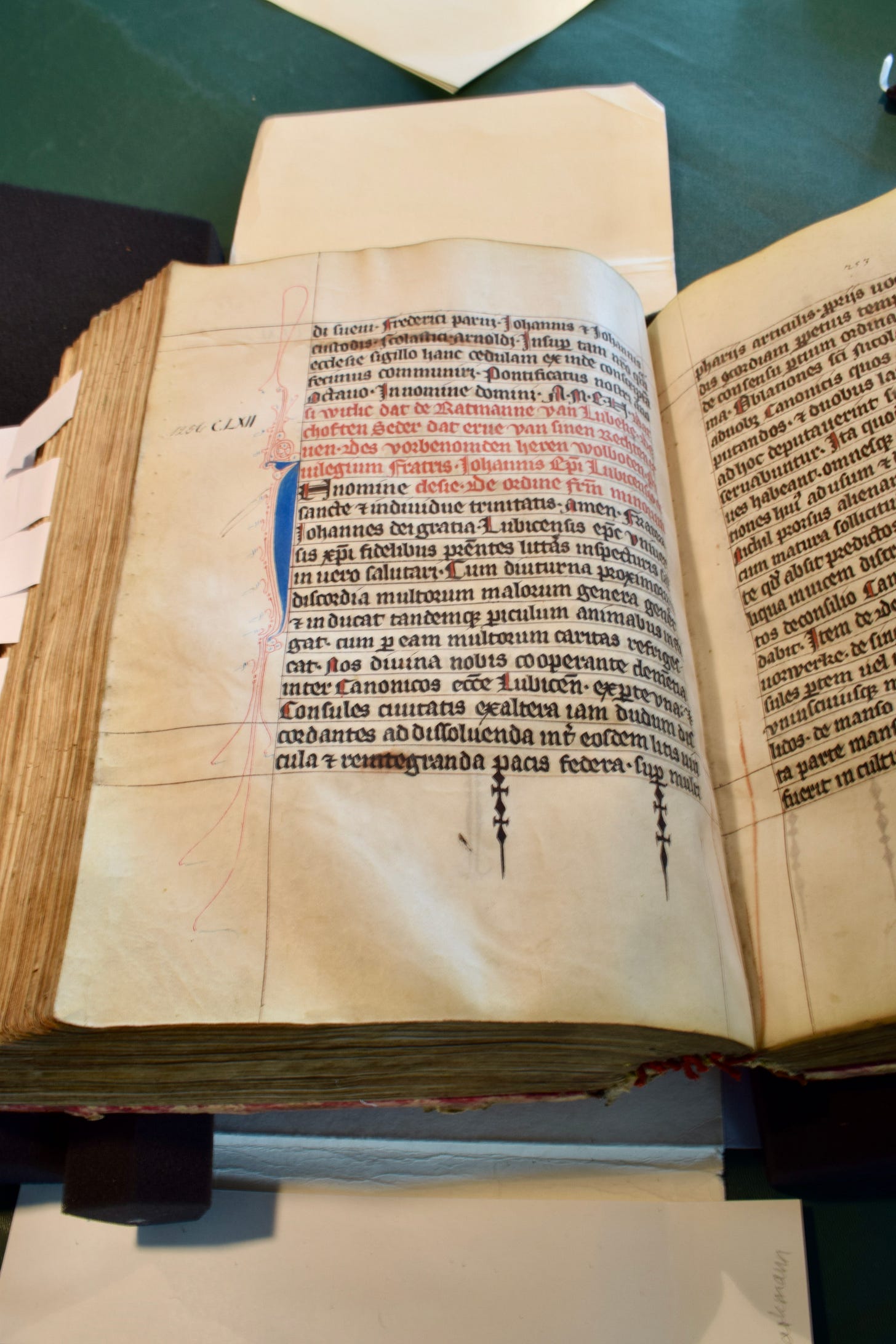

Albrecht Bardewik, Lübeck City Councilor and well-to-do textile merchant, is also Chancellor of Lübeck in 1299, when he commissions a cartulary book for Lübeck, Hs. 753 of the Lübeck Archive. To this day, it is still a kind of mascot for the city, judging by its prominence on the cover of the City Archive’s brochure entitled “Our City’s Memory”. Intended originally not just to record the city’s legal title, the Lübeck Maritime Law and a contemporary history or Zeitgeschichte known as the Bardewiker Chronik, it also served to help forge an identity for the city, a function which it still amazingly fulfills over 700 years later! It represented branding just as much then, as it still does now. While originally bound, formatted and started with its first slate of entries in 1299, city scribes would continue to make entries in a variety of scripts into the mid-16th Century. This is a living book rife with traces of use by city officials over the centuries. City scribes are second only to city councilors as important officials and also can act as foreign diplomats.

Bardewik’s Copiarius is a hybrid species of book that is impossible to categorize other than as a ‘city book’. It is a law book, but without the authority to legislate by the power of the pen, but instead by winning over the consensus of the communé through its impressiveness. The city’s most important legal title is copied into it from the original privileges so as to have access to their text without having to open the city’s treasure-keep, the Trese, built into the second floor of the St. Marien Church adjacent to the City Hall and Chancery. It is a book meant to be shown off. It is also a history book, but instead of giving a legendary account going back to the young city’s founding, it instead presents several contemporary occurrences in 1299, sometimes in a poetic way. It is the medieval equivalent of what today would be the news. The Chronicle (this unfortunate misnomer is attributed to it much later), is written in the vulgar language, Middle Low German, as is the Lübeck Maritime Law, also codified in the book. The codex’s vast bulk, the copies of legal title in the form of privileges granted by rulers, bishops, other cities and even popes, are mostly written in Latin with a few exceptions. Copies of the Barbarossa and Reichsfreiheitsprivileg of Friedrich II make up the first entries, being Lübeck’s founding documents.

The main news story reported in the Bardewiker Chronicle part of the codex, framing the other contemporary stories is the return of Lord Heinrich I of Mecklenburg in 1299 over Rome from Cairo, where he was held captive for 26 years. The sultan who frees him is likely Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad, who was reinstalled this year after considerable court intrigue. In the Chronicle, the Sultan is described as “milte”, not unlike "mild” in English but something more like its original meaning: moderate, munificent, generous, kind. Heinrich’s wife, Lady Anastasia of Pomerania, is named the daughter of Duke Barnhim of Pomerania-Stettin, which is in the neighborhood of Lübeck along the Baltic coast to the East. As Heinrich’s wife, she is described as:

syneme truwen leven wive frouwen Anastasian

his loyal and loving wife, Lady Anastasia

The story is introduced with a formulation reminiscent of epic poetry:

by desen tyden sande och vele Wunders in der werlde

during these times, there arose also many miracles in the world

We learn that:

Heinrich, Lord of Mecklenburg, the nobleman, was imprisoned in a tower in Babelonie (Cairo) over the sea for XXVI years on his way to the Holy Sepulcher on pilgrimage.

Anastasia spends 26 years awaiting the release of her husband, but does just not sit idly by, though. She rules over the small principality Mecklenburg in his absence and during the minority of her sons. This reign under trying circumstances goes mostly unnoticed except by local history buffs, who rightfully make Anastasia into a local heroine. Mecklenburg is really a ‘middle of nowhere’, to which few outsiders want to pay attention. It is located somewhere “behind the moon”, as the German saying goes. In the 19th Century, Otto von Bismarck said “Were the world to come to an end, I would move to Mecklenburg, because it takes 20 years for whatever happens in the rest of the world to arrive there”.

Mecklenburg as well as its Lord and Lady are, however, important to contemporary Lübeck merchants in 1299. They receive the reunited couple with great festivities upon Heinrich’s astounding return home. Before his ill-fated pilgrimage to the Holy Land, Heinrich is a patron of the pivotal port-city, donating the altar to the city’s newly-built church, St. Marien’s, the documents for which are copied into Bardewik’s Copiarius. Burghers are not at odds with their noble counterparts, but often are in alliance with them and can even act as intermediaries between them in conflicts. War is bad for business. Merchants want protection provided by local rulers on the roads and shipping lanes as well as assurance they won’t be abused by unreasonable tariffs imposed by their henchmen: the ‘herring-penny’ set too high. The oldest source regarding Heinrich’s return and reunification with Anastasia is Bardewik’s Chronicle. It’s ‘hot off the city scribe’s lectern’. The Chronicle functions to position the burghers in proximity to worldly rulers, conferring themselves a certain ‘elbow-rubbing’ high status. What else is known about Anastasia, though? Because of the unusual circumstances surrounding her regency over Mecklenburg during her husband’s long absence, we know much more than we do about other, more fortunate noblewomen.

With pragmatic literature taken into account, historians are not as distanced from the study of Literature as they often might think. The dialectic between fact and fiction is sometimes murky. The distinctions are not always unambiguous. Pragmatic literature is actually the historian’s bread and butter. If the study of History doesn’t envision establishing “the way it was” (aka 19th Century historian Leopold Ranke), but instead is intent on showing the way events were documented, then pragmatic literature is History’s life-blood. The sources historians rely on are, after all, specimens of pragmatic literature: legal documents like charters, deeds, letters and registers. Historian Anke Huschner did the work of poring over the archives in order to piece together a history of Anastasia’s life, published as an article in the journal Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher (2015).1

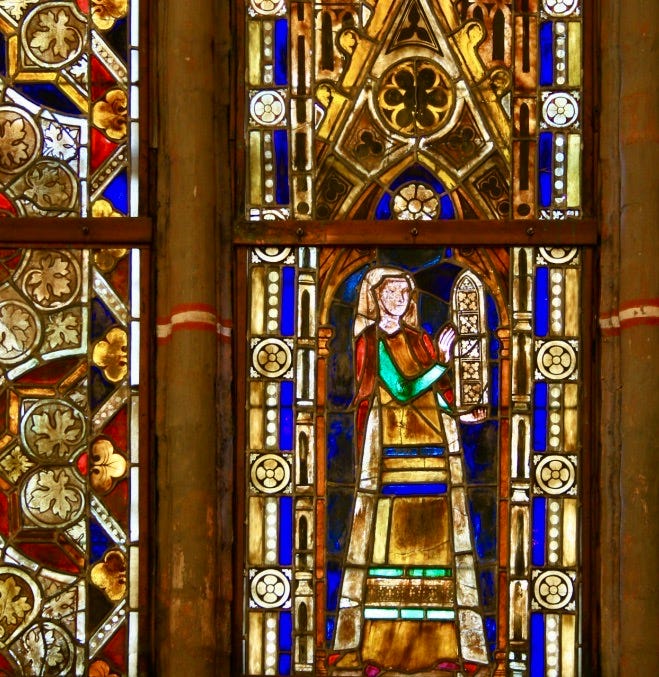

Huschner finds 24 legal documents issued by Anastasia between 1275 and 1314, bearing her seal. These documents arrange the conservatorship and tutelage of her sons, Heinrich II and Johann III, establish her own co-regency with her brothers-in-law and endow religious institutions like monasteries and churches with gifts such as stained glass windows. Already in the first year of her husband’s capture, 1275, she issues a document endowing Sonnenkamp Monastery, in which she is named ruler “domina Magnopolensis” in the absence of her husband “mariti nostri absentis fideliti gubernantes”. Her minor sons are named as future rulers. Her attached seal, resembling those of her stepmother and mother-in-law, bears the inscription, indicating her as ruler: ANASTASIE DOM[INE] MAGNOPOLENSIS. She is pictured holding both the coat-of-arms of her husband’s house, Mecklenburg, symbolized by a bull as well as the coat-of-arms of her own family, the Griffins or Greif family of Pomerania-Stettin.

Three years before Heinrich’s pilgrimage, both Mecklenburg and Pomerania found themselves already in conflict with the Margrave of Brandenburg. In this regard, Heinrich’s absence motivates Anastasia and her brothers-in-law, Johann II and Nicolaus, Dean (Propst) of Schwerin Cathedral, to form a co-regency together along with a group of six knights to hold off the Margrave. Her regency lasts successfully for 11-12 years until her son, Heinrich II, is old enough to take the reins of government in 1287. Anastasia stepping into this role as regent might seem unusual on one hand; noblewomen only found themselves so positioned in unusual circumstances like hers. On the other hand, it must not have been too big of an adjustment either. The wives of rulers kept their own separate courts and followings as well as their own separate residences, even in normal circumstances. Even after her son Heinrich’s II accession and her husband’s return in 1298, Anastasia keeps up her prominent role in the documentation. Heinrich lives only until 1302, just a few precious years following his miraculous return home. He surfaces in the documentation during this brief time only scantily. Anastasia survives as his widow another 13 years and continues to play a significant role, even during her son’s reign, especially as a milte patron of religious institutions.

It is perhaps no coincidence that Bardewik commissions his cartulary, including the contemporary history mentioning Anastasia, in the year 1299. This is the year in which the Lübeck burghers come into a white-hot legal conflict with the Bishop of Lübeck, Burkhart, which will last over a decade, one into which they are eventually compelled to drag the Pope (who takes their side). In the Chronicle, the city positions itself propagandistically in alignment with local rulers, like Heinrich and Anastasia, in order to shore up its own political capital. In 1299, the conflagration between the city and the Bishop becomes so bad, that he forbids the burghers entry to Lübeck Cathedral! Anastasia is, however, on good terms with the Lübeck Bishopric as a patron and is present in Lübeck during these hostilities. Although her husband Heinrich is just returned, she is the one who attempts to act as intermediary between the disgruntled parties.

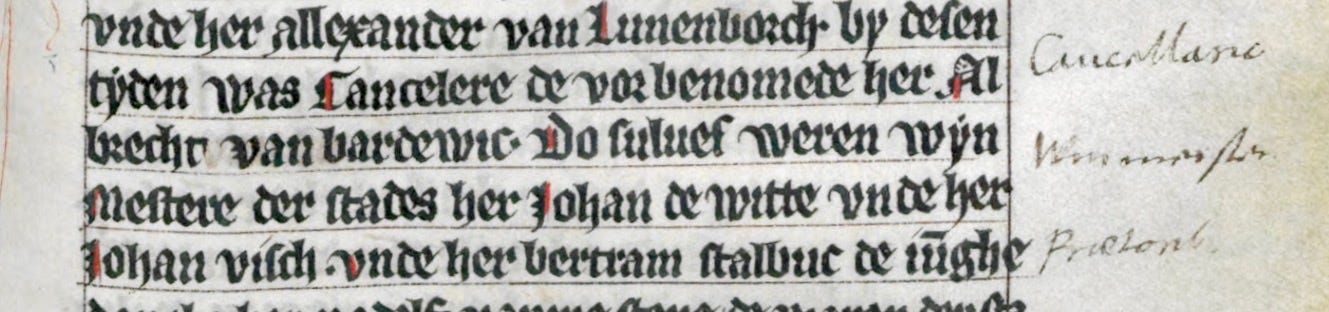

Legal documents give us factual information about all these events, but the narrative of the Chronicle gives us a more animated look at the lives of rulers from an urban perspective. It is hanseatic literature, as well as pragmatic literature. The Chronicle also seamlessly lists the current city office-holders: the Bürgermeisters, Treasurer, Marshall, Wine-Master, Mark-Master, Bailiff, Archivist, the Chancellor, Albrecht von Bardewik, much like the way the names of a monastery’s officers are recorded in a monastic cartulary. Lübeck’s official City Scribe, Alexander Huno, must have been involved in the creation of the Chronicle, if he didn’t write it himself, as well as in laying out of the codex. Scribes almost never give themselves credit in their work in the Middle Ages. Alexander Huno is, however, mentioned in the Chronicle, but rather in his capacity as diplomat. He happens to be in Rome as Heinrich I is released by the milte Sultan and meets with the Pope there, before returning North after his 26 year absence. He is a witness of events. Histories are both pragmatic in nature as well as literary.

The Chronicle serves purposes both concrete as well as more nebulous propagandistic ones. It reveals aesthetic elements like poetry and rhyme, while still documenting “the way it was”. The lauding mention of Anastasia in the Chronicle, missing from later Histories of Lübeck, ie. by Detmar, is underscored by the abundance of her appearances as domina in the historical record of legal documents. While a principality the size of Mecklenburg doesn’t have its own chancery at its disposal by a long-shot, Anastasia would have had access to a ‘circle of scribes’ in her surroundings to turn to, when wanting to issue one of these documents bearing her seal, much like Lübeck did before 1226 and the institution of its own chancery as the first imperial city. With connections through family in the clergy or to benefactor monasteries, Anastasia commissioned scribes to write these works of pragmatic literature, which are now historical sources, which prove her status. Mainly though, they are instruments through which she exercised her rule during her regency and her continued influence after 1299.

Anke Huschner, Anastasia von Pommern, Herrin von Mecklenburg (1264-1317), Spielräume und Lebensführung einer Mittelalterlichen Fürstin. in: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher No. 130, 2015, pp. 7-44

Really interesting piece!

Very interesting article. I was wondering if the article Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher about Anastasia is found in English. This is a great supplement to your article.