The Lay of the Nibelungen and Divination, Pragmatic Literature Part 8

Mermaids, Crossing the Danube and Civil Law

The literary canon tells us: no Goethe’s Faust, then no modern German Literature; no Nibelungenlied, then no medieval German Literature. Because the beauty of the Nibelungenlied’s poetry is self evident, 19th Century nationalist projects sought to exploit it. Richard Wagner’s three Opera cycle, the Ring of the Nibelungen, makes an apt example. Scholars from his same Romantic era attempted to construe out of the Nibelungenlied a national epos corresponding to the Romans’ Aeneid. Vergil poetized under the patronage of Emperor Augustus and Maecenas to forge a Roman identity with his Trojan origin story of the Roman people. Eager to emulate this kind of national identity for German speaking people lacking one, editors craftily manipulated the Nibelungenlied’s structure to resemble the Aeneid’s structure, arbitrarily dividing it into books, which are not reflected in the manuscript witnesses.

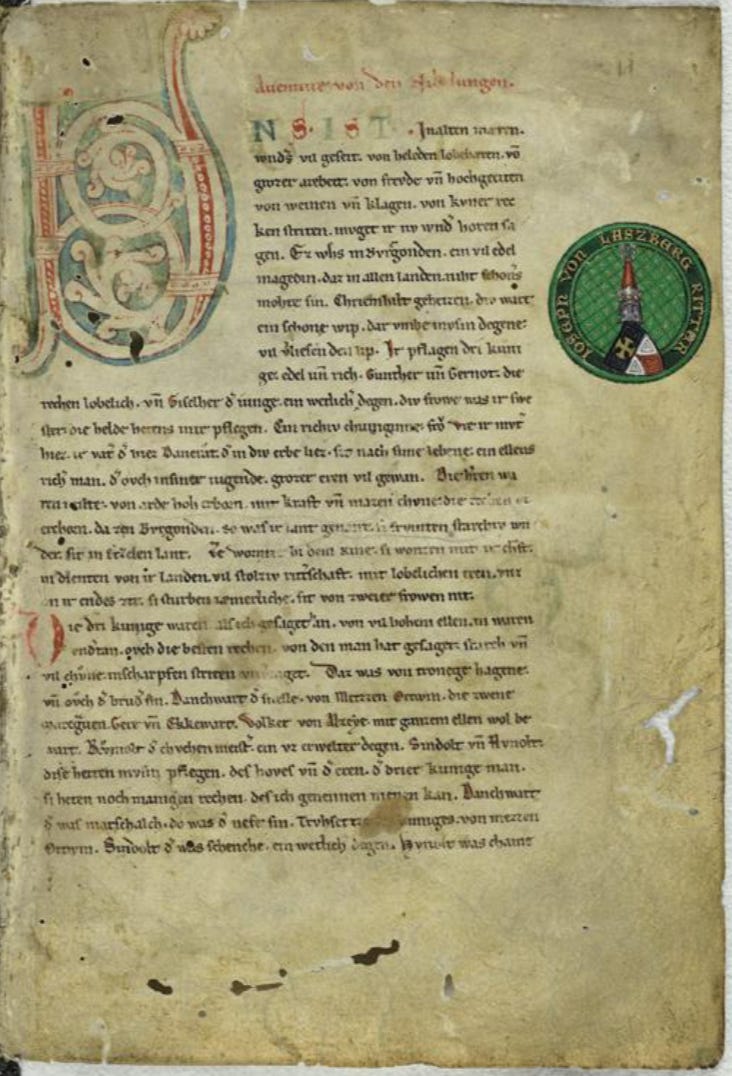

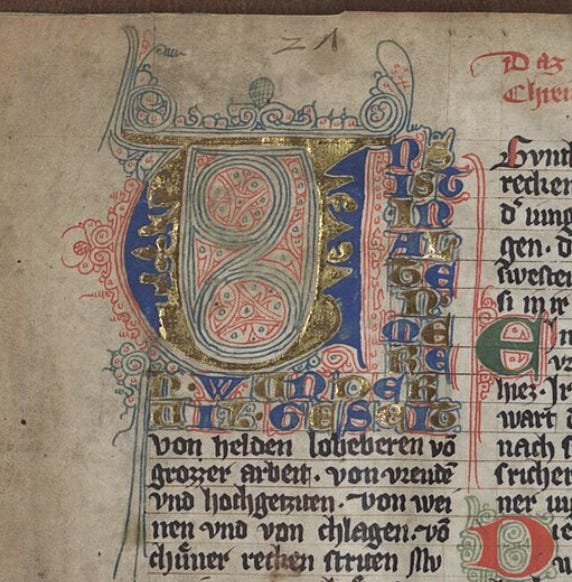

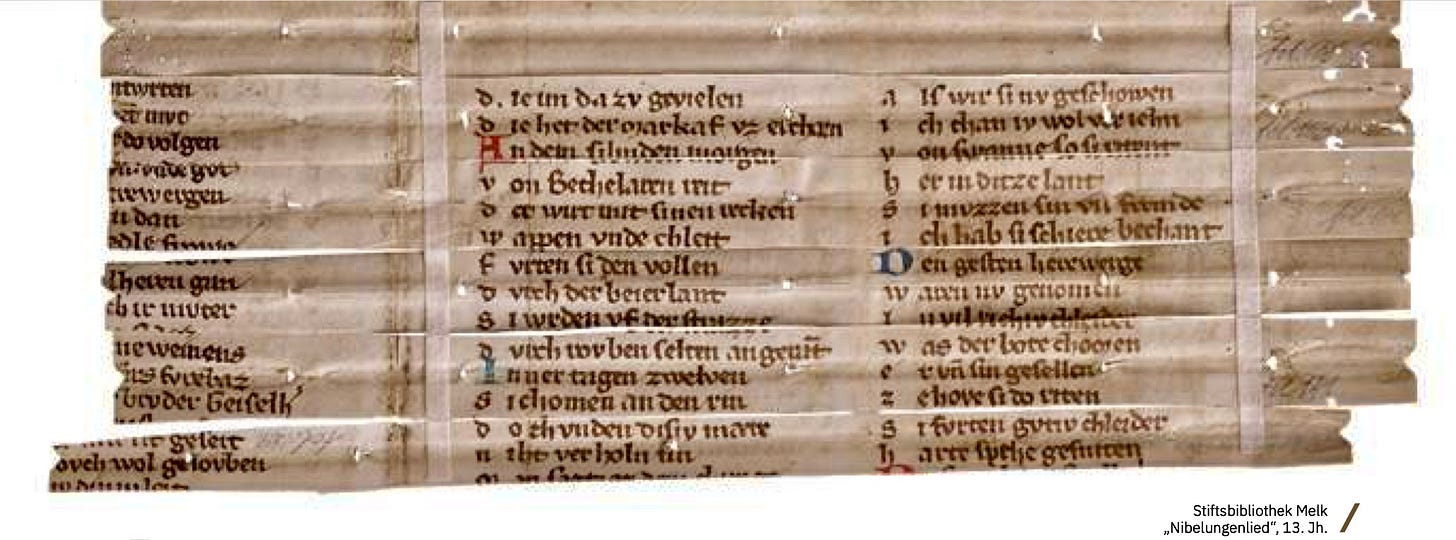

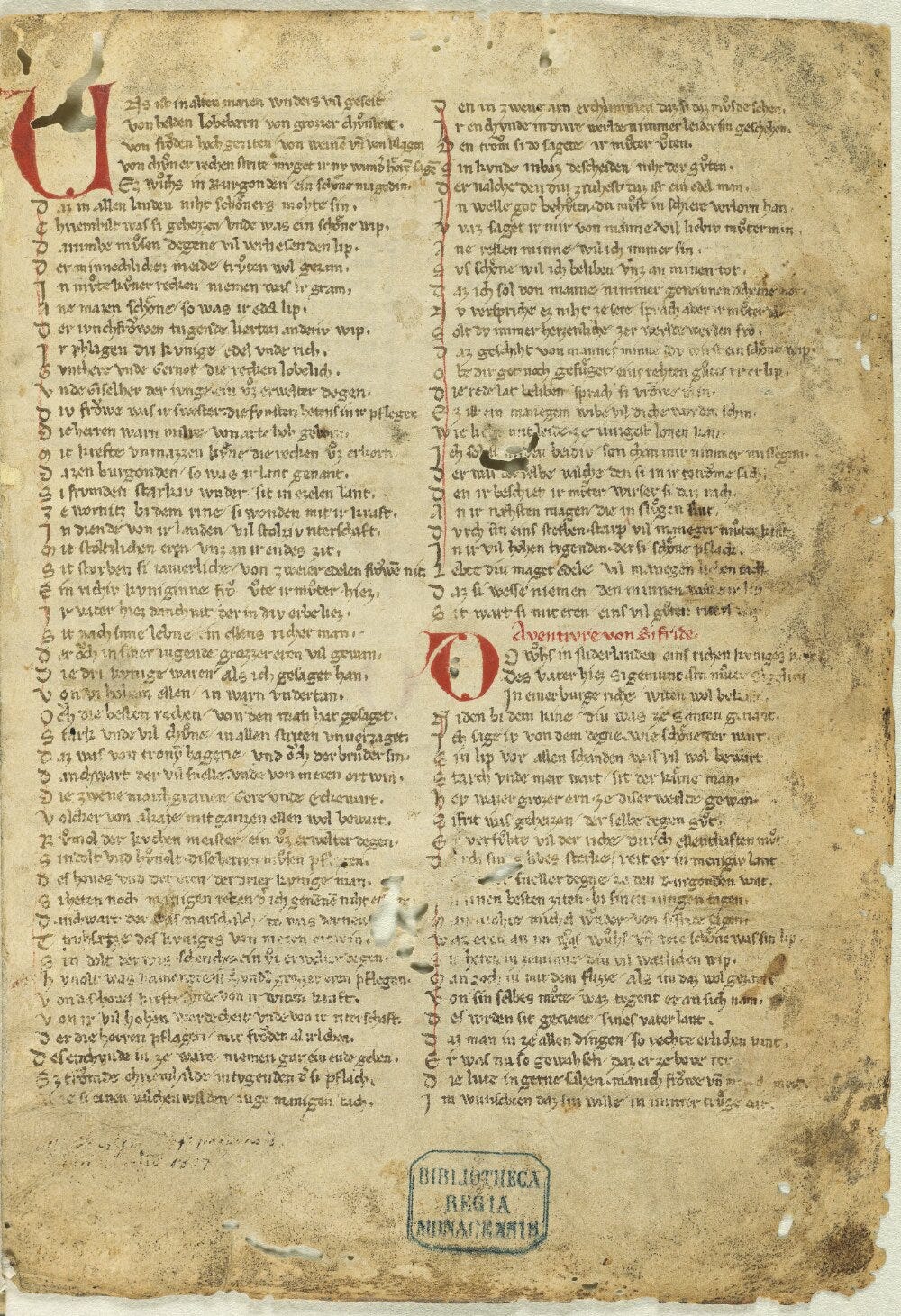

The A and C families of Nibelungenlied manuscripts (content of the A,B,C,D et al versions varies greatly) begin in the first stanza with an introductory auctoritas topos similar to those found introducing Beowulf and Hildebrandslied, appealing to and feigning a supposed oral tradition of heroic lays while directly addressing the audience:

Uns ist in alten meren | wnders vil geseit

von helden lobebæren | von grozzer arbeit

von vreude vnd hochgeziten | von weinen und von chlagen

von chuener recken striten | muget ir nv wnder hœren sagen

Of marvels are much told | to Us in old tales

Of warriors worthy of praise | of great calamity

Of joy and festivals | of tears and bitterness

Of brave knights in battle | now may you hear of marvels told

The verse form of the Nibelungenlied echoes that of the heroic alliterative long line divided into two half lines known from Beowulf, lending the poetry a melodic cadence suited for reading aloud. The Burgundian princess Kriemhild is the first figure introduced, implying a female main character. To avert any possibility of suspense and to deliver the spoiler of all spoilers, we learn in the second stanza already:

diu wart ein schone wip | darumbe musin degene | vil verliesen den lip

She was a beautiful woman | that is why many warriors will | have to lose their lives.

Like perhaps the greatest figure of mythos, Helen of Troy, her great beauty gives rise to the story’s tragic end, also making her a dichotomous figure.

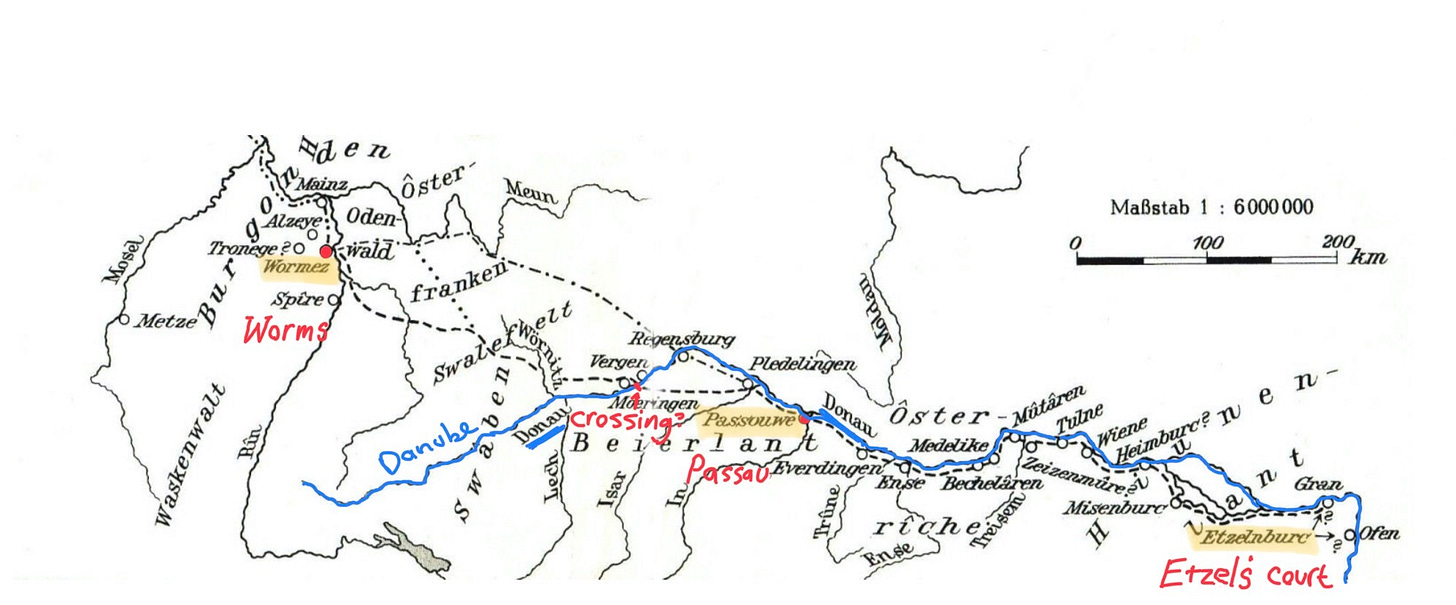

Like many great epics, the Nibelungenlied, set in the 5th Century during the reign of Etzel — the historical Attila the Hun — consists of two main plot strands. In the first, the hero, prince of Xanten in the Netherlands, Siegfried the dragon-slayer, woos the Burgundian princess Kriemhild and sails to Iceland to arrange a conjugal alliance between the Burgundian King Gunther and the Icelandic princess, Brünhild. A double marriage ensues at the Burgundian court in Worms on the Rhine. Brünhild, gripped by wounded pride and jealousy towards Kriemhild over Siegfried, manipulates her husband Gunther to treacherously invite him to a hunt upon which his vassal, Hagen von Tronje, callously murders him by a spring. If Brünhild cannot have Siegfried, she can not allow Kriemhild to have him either.

While Siegfried’s reputation as a dragon-slayer is obviously fantastical, there are numerous references to him predating the Nibelungenlied. There is nothing to prove he may not actually have been a living quasi-historical figure.

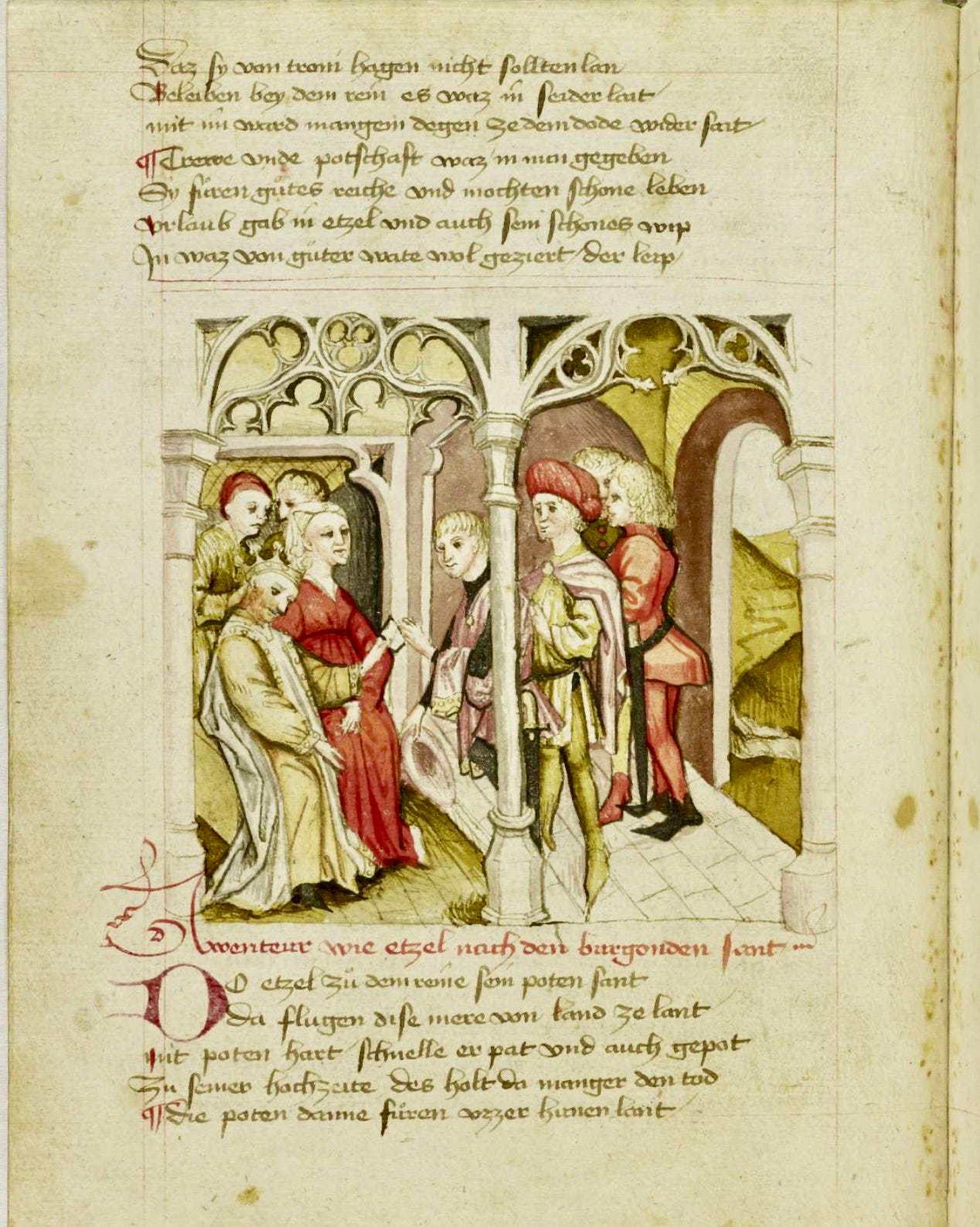

In part two, Kriemhild, now widowed and remarried to Etzel and residing east of the Danube in Hungary, correctly deduces the identity of the perpetrators of Siegfried’s murder. With underhanded, vengeful intent she invites the Burgundians to a festival — hôchzît — at Etzel’s court in Hungary. Now possessed by vengeful blood lust, she plans the ambush of her guests, including her own brothers. Kriemhild appears in part two as an altogether different figure as the kind, loving figure she is in part one.

Unsuspectingly, the Burgundians accept her deadly invitation. They travel, accompanied by the mysterious cadre the Nibelungen, in the direction of the Danube, which they must cross to enter Etzel’s realm. The great river presents them with a natural boundary, but also a last point of return before meeting their fate. Like in Parzival, a water crossing represents transversing Foucault’s hierarchy of places, but quite unlike Parvizal’s ascension of spatial hierarchies towards his self-realization, the Burgundians instead descend spatial hierarchies into the depths of their ultimate undoing (see parts 6 & 7 of this series of posts on medieval spaces).

The party of Burgundians and Nibelungen finds the Danube flooded with high water, impeding their progress, already a foreboding omen. As Hagen seeks alone to find a way to get the party across, a pivotal scene unfolds in which he encounters two mermaids, Hadeburc and her niece, Sigelint, floating like swans in a “beautiful spring” near the Danube. Iliciting an ‘uncanny valley’ effect, the mermaids somehow immediately know who Hagen is, as well as his objective, addressing him by name: Hagen, Aldrîânes chint — Hagen, Aldriane’s son. Like an oracle, Sigelint prophesies to skeptical Hagen that no one in his party will ever return to Worms alive, save his lord Gunther’s chaplain.

kümestû hin zen Hiunen | sô bistû sêre betrogen

Jâ soltû kêren widere | daz ist dir an der zît

wand ir helde küene | alsô geladet sît

daz ir sterben müezet | in Etzelen lant

swelche dar gerîtent | die habent den tôt an der hant

niuwan des küneges kappelân | daz ist uns wol bekant

der kümet gesunt widere | in daz Gunthêres lant

If you make it to the Huns | then you are very deceived

You should turn around | there is still time

If you brave warriors | accept the invitation there

Then there you must die | In Etzel’s land

Towards which you ride | your death is at hand

No one but the King’s chaplain | it is well known to us

Will ever return alive | to Gunther’s realm

Hagen mistakenly shrugs off the mermaid’s prophesy, but does, however, pay attention to her directions to the ferry which can carry the Burgundians and Nibelungen across the Danube. Hagen finds the ferryman, Etzel’s pledged servant, on the opposite shore and calls to him, misrepresenting his identity as one of Etzel’s followers to lure the ferryman across the great river. Irritated by the deceit, the ferryman proudly refuses to take him across for any amount of gold. Hagen then chooses to cross a legal boundary to facilitate the crossing of a natural one by beheading the uncooperative ferryman with his sword in a frenetic effort to commandeer his boat.

As Hagen returns to the traveling party with the boat, Gunther is suspicious about the blood, still warm, awash on its decks. Regardless, Hagen ferries a thousand knights and nine thousand pages across the Danube, challenging any sense of rational logistics. In a vainglorious effort to put the mermaid’s prophesy to the test and to prove it untrue, Hagen attempts to kill the chaplain by drowning, throwing him into the turbulent water. Although the chaplain cannot swim, “God’s hand” helps him to safety on the other shore. From this sign, Hagen immediately knows the mermaids were indeed right about the fate he shares with the Burgundians: none left among them now will survive the journey. However, having crossed these boundaries, there is no return to safety for them. There is instead only the foreboding of doom. Hagen’s thoughts echo word-for-word the ominous foreshadowing from the second stanza: “many warriors must lose their lives”. From this point onwards, it is as though he is set on proving the mermaids right.

Da stund der arme prister | und schawet sein gewant

Da bey sach wol Hagen | daz ez war ungewant

Daz im e da sagten | dy weisen merweip

Er gedacht dise degen | müsen verlisen den lip.

The poor priest stood there | and shook [the water from] his clothes

Thereby Hagen saw | that it was true

What they told him | the wise mermaids

He thought: this warrior | must lose his life

Outraged by Hagen’s transgressions and wanting to rectify the wrongs perpetrated by him, his lord Gunther calls a promise out to his chaplain from across the Danube: ez wirt euch wol gebüßt | waz euch hat getan — “you will be well compensated | for what was done to you”. The word büßen, a legal term — to pay a fine, i.e. for damages — occurs often in the Sachsenspiegel, the legal bestseller discussed in the preceding part 7 post. Gunther does not yet know that the chaplain has already been compensated with his life and that Hagen and the entire party will have to pay with theirs.

After Hagen reveals the mermaid’s prophesy to the party, Gunther’s vassal and companion, Gelphrat, the Margrave of Bavaria, also begins to question the legality of Hagen’s actions. Gelphrat suggests Hagen should not come away unscathed in the wake of his crimes, but instead should be held accountable and taken into custody until a judgement is rendered — bürge or pürge — means something like bond, bailment or guaranty, by which someone is surrendered pending the adjudication of a legal question, in order to hold the peace for the meantime. The Burgundians are aware Etzel could well answer in kind for the murder of his servant, the ferryman, if proper legal proceedings are not followed and Hagen is not given up. His continued rampages will, however, forestall this effort.

I know well, spoke Gelphrat

As Gunther and his followers rode past

That Hagen’s from Tronje hubris

would bring us to grief

Now he should not come away unscathed

For the ferryman’s death

This fighter must be taken in as guaranty [pürge]

While Gunther and Gelphrat recognize the injustice unfolding around them at Hagen’s hands, Hagen himself does not show the least sign of remorse nor any misgivings for his ill deeds, repeating his same tone after murdering Siegfried by the spring. He clearly knew his actions were punishable then, as he kept his culpability secret while stealthily laying Siegfried’s corpse at Kriemhild’s door. He hid himself the legally allotted amount of time to not be caught literally ‘red handed’ — auf frischer tat.1 Still, he never displays a guilty conscience at all. This pattern persists after his crimes on the Danube. If there might be any possibility to still avert the prophesied disaster, Hagen’s unwillingness to acknowledge and atone for his crimes prevents it. He lacks the intuitive knowledge of justice, which Gunther and Gelphrat possess.

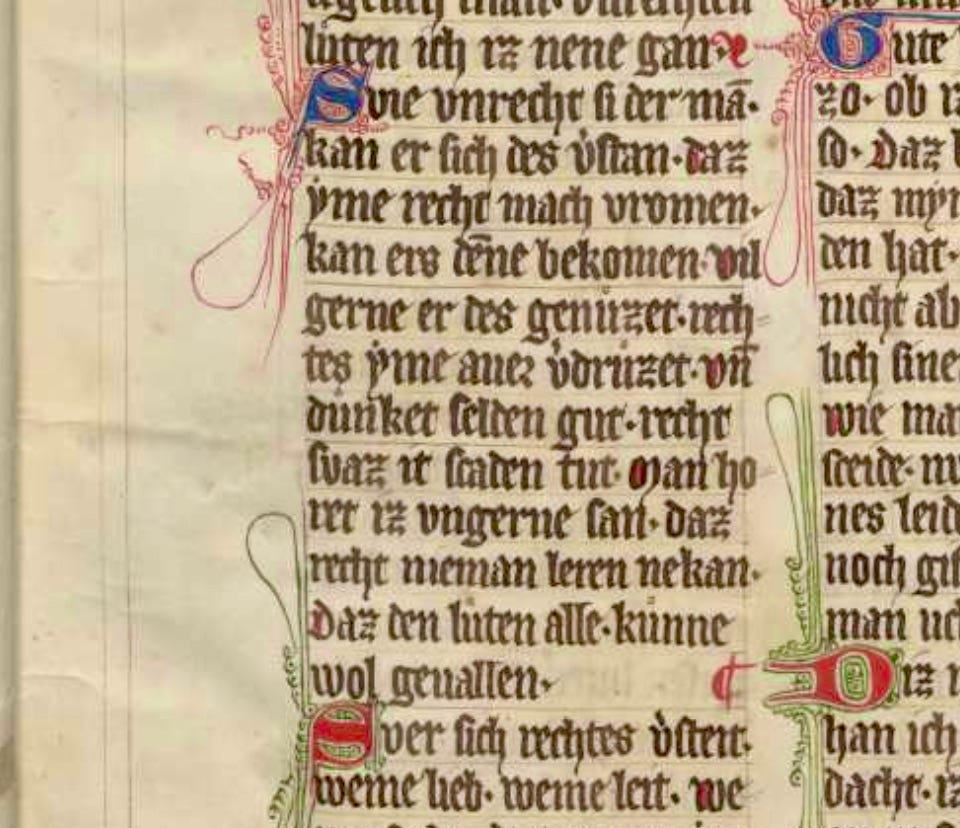

Law is not law because it is written in books in the Middle Ages but instead because God is selven reht — God is himself the law. In the prologue of the Berlin mgf 10 manuscript from 1369, the Sachsenspeigel thematizes the idea that a healthy conscience and devoutness towards God are one and the same. Although a law book, this manuscript’s outstanding gothic textualis script and French style initials with fleuroneé decoration are indistinguishable from those of prayer books as well as courtly epics like the Nibelungenlied. Genre is not discernible at a glance.

Whosoever is an unjust man ·He can come to understand ·

That justice makes him devout ·

This he can figure out ·

Very much can he gladly use it ·

But if justice instead bothers him ·

One considers it seldom good ·

When damages occur. It is instead just ·

When one is displeased to hear of it ·

No one can teach what is just ·

So all people’s fate falls well to them ·

The last Middle Low German word — gevallen — is more than fitting in this legal context, as well as in Hagen’s story of the prophetic judgement passed upon him by the mermaid, Sigelint. It means the due fate which falls to one. In the Middle Ages, elements of fate and divination are intrinsic to the word’s use. In Old English, befællan means to fall to, or to befall one. The modern English idiom ‘fall to one’s lot’ is similar, as it suggests consequences of the unavoidable. Faellen means to pass a judgment in Middle High German as well as in modern German.

In Antiquity, oracles like the mermaids are the equivalent of judges who pass sentence. The mermaids not only saw through Hagen’s heart, they knew what he had perpetrated against Siegfried as well as what he would soon do to the ferryman as well as attempt to do the chaplain. The mermaid’s ultimate premonition is of dire consequences for all Hagen’s misdoings. Prognostic texts, which deal with divination, represent yet another branch of knowledge inherited from Antiquity, which is preserved and curated by medieval monasteries.

Not understood by the Nibelungenlied poet as overtly pagan or un-Christian in nature, divinatory foretelling by pre-Christian mythical figures does not suggest the tradition of old orally transmitted Germanic heroic songs, never mind that the Nibelungenlied represents a pagan work. It emerges from a religious scriptorium and is peppered with knowledge only accessible to literate, educated, religious monks and nuns. Pagan imagery is instead used harmlessly to anachronistic effect and is not intended as any kind of endorsement.

The likely patron of the Nibelungenlied poet is revealed in its sequel, Die Klage, as Wolfger, the Bishop of Passau: “The song sung about the Nibelungen, sung and beautifully told, Wolfger, the Bishop of Passau did this”. Wolfger von Erla did actually occupy this office 1191-1204 and was known to patronize vernacular poets like Walther von der Vogelweide. In the High Middle Ages, pagan knowledge and imagery are, depending on the time and place, not normally forbidden or seen as problematic by most bishops, who, along with abbots and abbesses, command the cultural production of scriptoria.2 Intolerance and exclusion of pagan material is, in general, much more of an Early Modern phenomenon, although some make efforts earlier to rehabilitate it with a christianizing sheen instead of to throw it out.

There are certainly pagan elements portrayed in the Nibelungenlied, the most blatant being the mermaids, who are indeed pre-Christian Celtic mythical figures who inhabit inland bodies of water, especially springs. The interpretation of an un-Christian intent in casting them in the story rests, however, upon false inferences. The story set in the 5th Century is told counter-historically before the backdrop of 13th Century Christian religiosity. The Burgundians were a Germanic tribe settled along the Rhine at Worms in the 5th Century who practiced Arianism, but they were nothing like the Christian knights the poet makes them out to be. They were not defeated in Hungary, but were instead driven from Worms and then forcibly resettled near Lake Geneva. Precise historic realism is not remotely attempted by medieval poets (and can even appear to be optional for chroniclers). For example, Atilla and Theoderich (Dietrich von Bern) appear as contemporaries in the Nibelungenlied, but did not, in fact, live at the same time. Details of the story are ‘modernized’ to 13th Century standards. The characters are ‘knightified’.

In part one of the epic, the queens Kriemhild and Brünhild come into a heated dispute (over Siegfried and their relative status) while going to attend worship service at Worms Cathedral, which is yet to exist in the 5th Century. The scene is rife with religious detail. The story plays out in the time between Roman rule and the creation of the Worms Bishopric in the 7th Century and nearby Lorsch Monastery in the 8th Century. However, much of the picture the poet paints is of his/her contemporary world, not the world 700 years earlier.

The legal considerations examined here also are typical of the dawning High Middle Ages at the exact time of the epic’s emergence, not of the 5th Century. Emperor Friedrich’s II Landfrieden doctrine, discussed in my preceding part 7 post, was just being promoted during the Nibelungen poet’s time. It sought to ban the old practice of the feud and to replace it with court proceedings and legal remedies, which were supposed to stop endless cycles of bloody revenge.

Most of the research into legal knowledge encoded into the Nibelungenlied deals with Kriemhild’s revenge, but mention of such contemporary legal terms as büßen, bürge, eit swern — swearing an oath, are found in countless contexts throughout. The Nibelungenlied slightly predates Eike von Repgow’s vernacular Sachsenspiegel, so the Nibelungen poet could not have had access to it. Still, the poet was clearly very well read in multiple branches of knowledge in Latin language, including law. Many pagan Classical works were represented in the library of Niedernburg Monastery in Passau, i.e. Pliny, Martianus Capella, Vergil and Seneca as well as the most important natural science, medicinal and theological works. Pliny notably handles prognostic themes, which take shape in the mermaid’s prophesy. Niedernburg is founded as a Benedictine convent in 772 at the confluence of the Inn and the Danube in Passau. Of all the many geographical references in the Nibelungenlied, those in the environs of Passau, through which the Burgundians and Nibelungen travel, are described with the most detail.

In upcoming part 9, I will return to the theme of legal texts as examples of pragmatic literature, specifically oaths. While the majority of medieval manuscripts are lost, recycled or destroyed, there are others, which never came into existence. There are parchment leaves formatted, but intentionally left blank. Their emptiness also tells a story. Remember, parchment is extraordinarily expensive in the Middle Ages and is almost never left unwritten.

Timo Renz, Um Leib und Leben, ‘Knowledge about Gender, Bodies and Law in the Nibelungenlied’, Berlin/Boston 2012.

Stephen Jaeger, The Origins of Courtliness, Philadelphia 1985.

Great analysis.